Honoring Mandela, PSLS is proud to provide legal support to growing BDS movement

/Reflecting on the meaning of Nelson Mandela's legacy, Palestine Solidarity Legal Support redoubles our commitment to providing legal advocacy to the growing Boycott Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement in the United States.

We are honored to support those who actively work to end the system of "pass laws", "bantustans", and legally enshrined inequalities that Palestinians face daily, comparable to the system of oppression that Mandela fought against in Apartheid South Africa.

A leader of the current student movement for Palestinian rights,

Rahim's piece explains how today's divestment campaigns on US campuses continue the legacy of the divestment struggle to end apartheid South Africa. PSLS is proud to provide legal backup to the boycott and divestment movement, and considers Mandela's legacy and the anti-Apartheid struggle around the world as a beacon for all working for freedom and justice in Israel/ Palestine.

December 9, 2013, By Rahim Kurwa, active member of Students for Justice in Palestine and currently a graduate student in the Sociology Department at the University of California, Los Angeles.

In today’s edition of the Daily Bruin you can read wonderful interviewswith Professors at UCLA who were a part of the 1970s and 1980s struggle against apartheid in South Africa. Apartheid is the term coined by whites in that country to refer to a political system in which whites systematically dominated the native black population - using a comprehensive set of separate laws to keep the black population unfree and unequal. The paper also includes a warm essay by Eitan Arom reflecting on the University of California’s relationship to Mandela, how he and Winnie Mandela were seen as inspirational figures, how the anti-apartheid movement helped UCLA discover its "moral center," and how the fight for South African liberation awakened a sense of internationalism among UCLA students.

Arom’s essay includes a prayer that "we can only hope to see with the same moral clarity as [Mandela] did, or at least for leaders like him to open our eyes when we don’t."

Today, however, we have an opportunity to put the lessons of Mandela and South Africa into practice by looking at the question of Palestine with the same moral clarity.

In 1974 there were pass laws that restricted where blacks could travel within their country. Students protested Polaroid, the company that supplied the film to create the pass-books that repressed millions on the basis of their skin color. Today, Hewlett Packard operates an analogous system in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, providing the biometric identification systems used to restrict the freedom of movement of Palestinians in their own country.

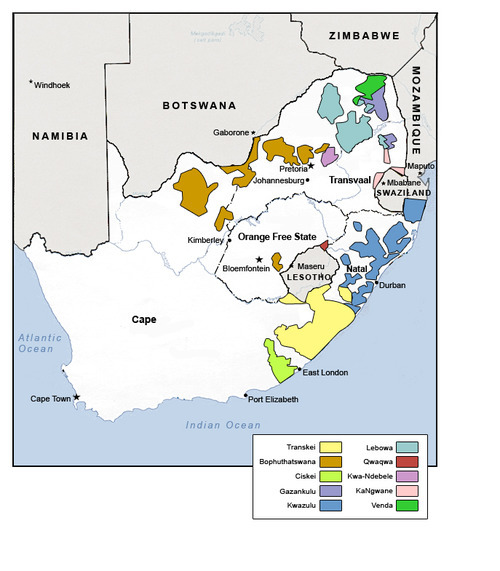

In 1974, there was a network of blacks-only areas, known as “bantustans,” outside of which blacks were not allowed to go. These bantustans were turned into independent black mini-states, cut off from each other and denied access to the resources of the South African state. Today, the West Bank is carved up into much the same network of isolated islands, cut off from water resources, fertile lands, and each other. Those islands are surrounded by a system of segregated roads and a network of checkpoints and walls (that we are invested in) that attempt to make their isolation permanent. Comparing the Palestinian territories in the West Bank to the bantustans from South Africa’s past, South Africa’s International Relations Minister Maite Nkoana-Mashabane said ”the last time I saw a map of Palestine, I couldn’t go to sleep…It is just dots, smaller than those of the homelands, and that broke my heart.”

Bantustans in South Africa

The West Bank’s Palestinian areas:

In 1974, blacks in South Africa were systematically denied the right to education, the right to vote, the right to a fair judicial process. Today Palestinians yearn for the same basic equalities.

In 1974, the University of California was invested in many American corporations that did business with and propped up the apartheid system. These companies were happy to sell the apartheid government whatever it wanted, at a steep price, and the University of California invested in those companies because it knew it could get a high return on its investment.

Students at the University of California, led by figures such as Tim Ngubeni, Sam Law, Pedro Nogueira, and hundreds of other women and men whose names have fallen from the historical record, recognized their complicity in this oppressive system. They understood that it was their obligation to stop the University of California from investing in American companies that supported apartheid. From approximately 1974 to 1986, they organized to force the UC Regents to divest from South Africa. It required no small measure of moral clarity to work day after day to achieve something that was not promised, and for a long time never seemed likely to happen.

As we mark the death of Nelson Mandela and think about his legacy here at UCLA, we must recognize that 1974 and 2014 are not so different. Today we are investing in a very similar kind of apartheid. A new set of corporations are providing the goods and services that are required in order to deny Palestinians the same basic freedoms that blacks in South Africa were denied for so long. And a new set of students are joining the divestment movement across the state. If Mandela’s legacy lives on, it must be in our constant effort to understand our relationship to systems of oppression. It must be in our struggle for divestment from oppressive systems like the prison industrial complex in our own country and the apartheid system operating in Palestine today.

It should come as no surprise that there is a long history of South African solidarity with the Palestinian people, who like black South Africans are jailed, beaten, and killed while struggling for their own freedom. Nelson Mandela expressed his solidarity with the Palestinian struggle in simple but compelling terms. Today, Desmond Tutu actively supports the divestment campaigns of SJPs at the University of California, and Ahmed Kathrada, who spent 26 years in prison alongside Mandela, works to free Palestinian prisoners subjected to conditions he, Mandela, and many others once faced.

In the same interview in which she compared the situation in Palestine to her country’s own past, Nkoana-Mashabane declared that "the struggle of the people of Palestine is our struggle." Today we must join her in solidarity with the Palestinian people, or else bury the legacy of Nelson Mandela.